﷽

I will begin where Allah ﷻ begins, and start with the organizational study of the greatest sūrah of the Quran, Sūrat al-Fātiḥah (The Opening)1,2. Even the seasoned reciters of this sūrah may be surprised at the amount of depth in its structure.

Sūrat al-Fātiḥah is unique in that it is said to have been revealed twice3, once in Makkah, and again in Madinah. It is the sūrah that Muslims recite in every unit of ritual prayer, and the most comprehensive in its summary of a person’s relationship with Allah ﷻ.

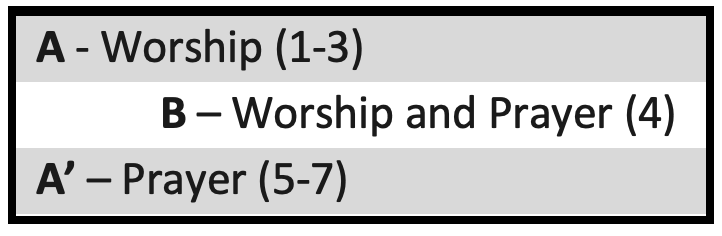

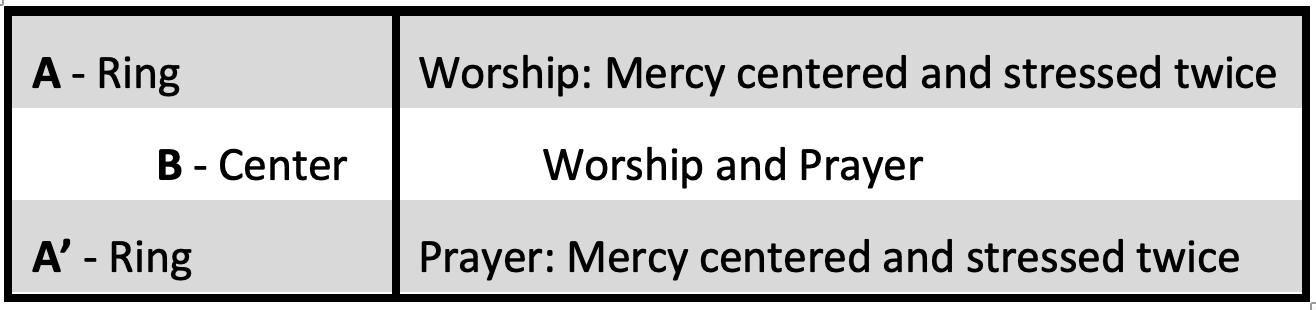

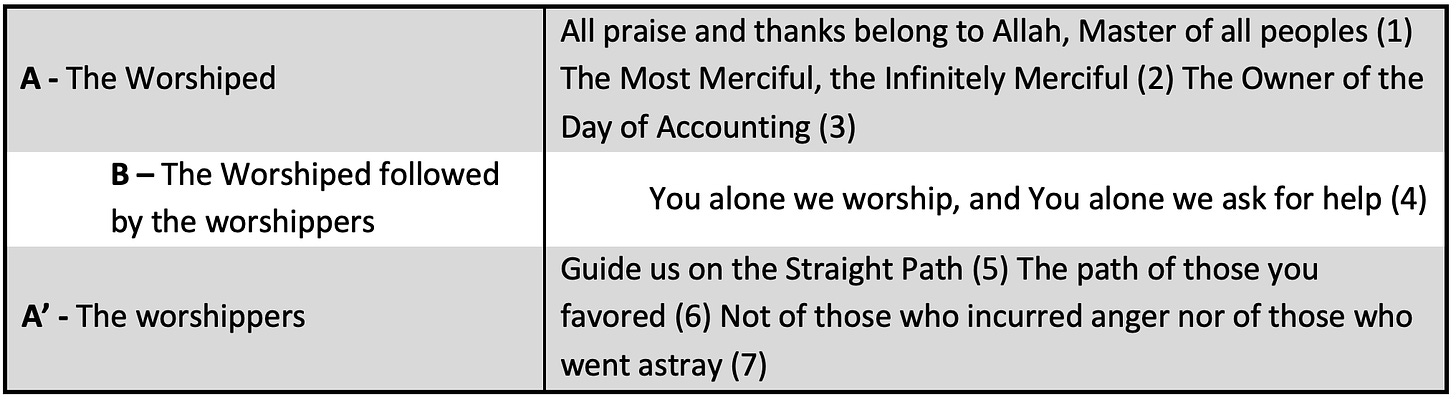

Taking a macro-view of the entire sūrah, it appears to be organized in a ring structure, with the theme of worship permeating throughout4.

I am numbering the āyāt based on the opinion that the basmalah5 is not a part of the sūrah. Perhaps the following analysis can act as further proof of this opinion being the correct one6.

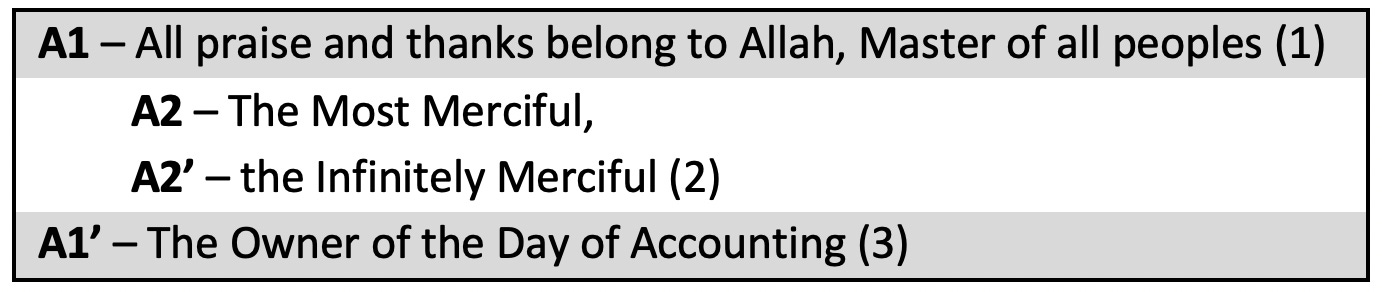

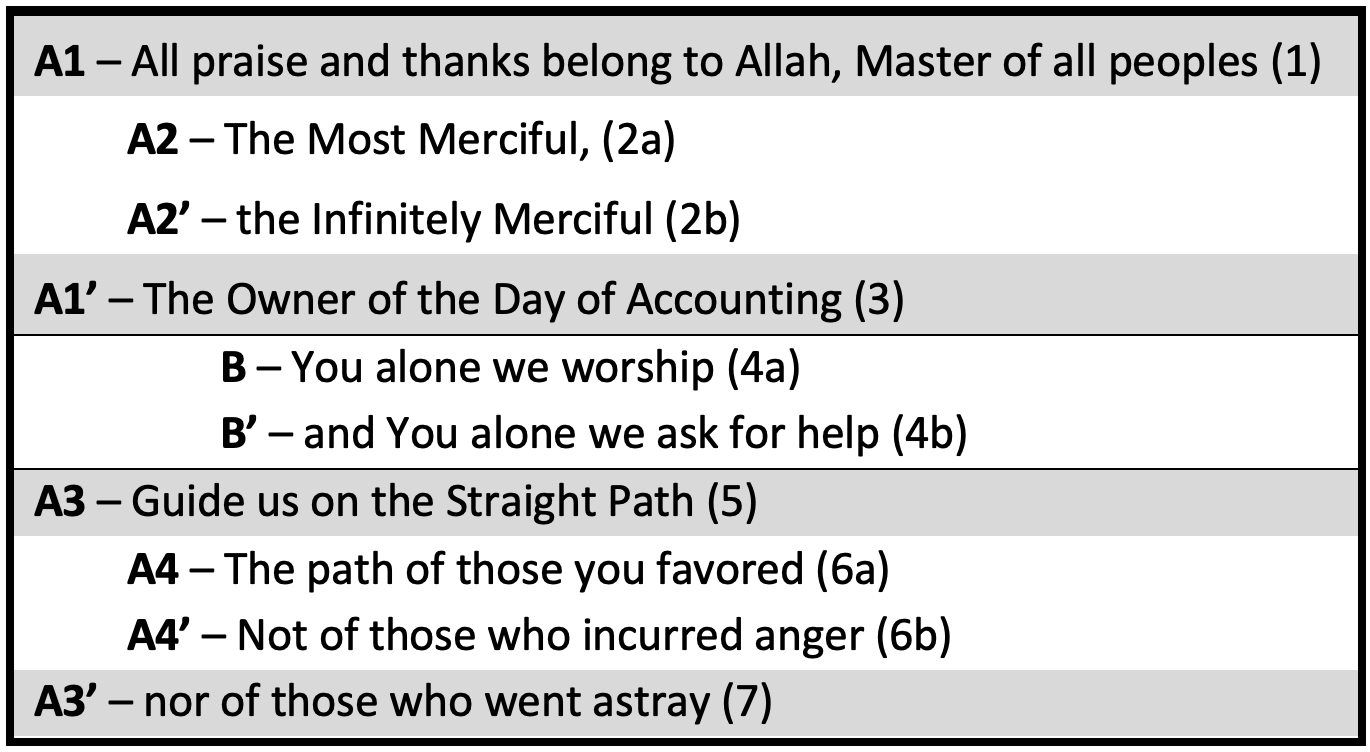

Breaking the macrostructure into its individual components, it seems that Section [A] can be laid out into its own ring structure.

Section [A] – Worship (1-3)

Grammatically, these āyāt are actually one continuous sentence. Allah ﷻ begins and ends the ring with mention of His amazing attributes and sandwiches two references to His mercy in-between. This ring describes the One worthy of being worshiped.

Summarized more succinctly, this ring can be shown as:

The next āyah, constituting all of Section [B], is a nice two-part sentence that perfectly transitions between the first and last ring. The statement of “You alone we worship,” links back to the first sentence (Section [A]) and the second half, “You alone we ask for help,” connects to the next section, Section [A’].

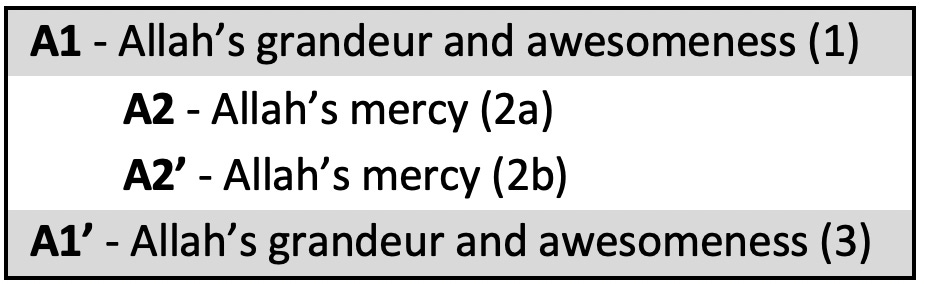

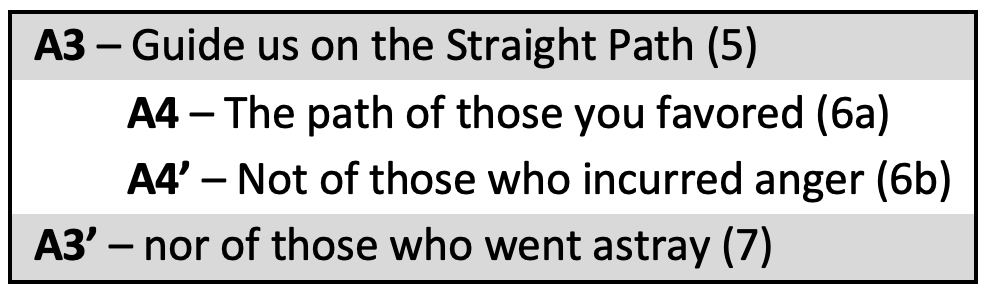

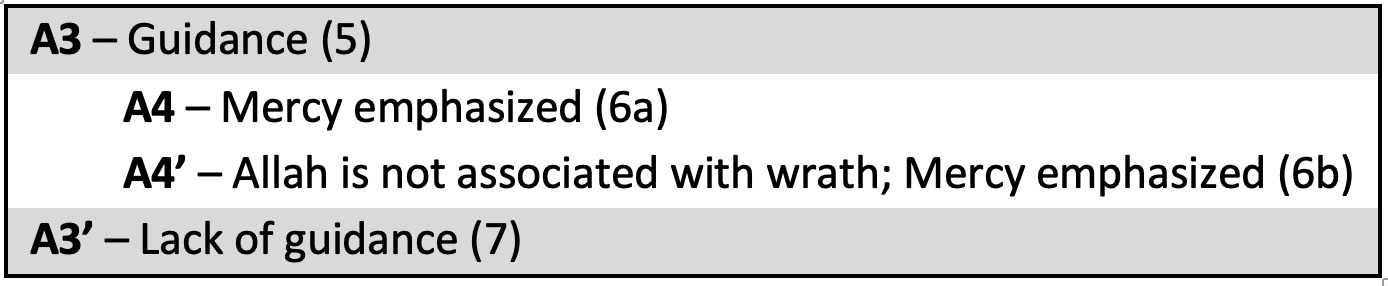

The final three āyāt also appear to form a small ring:

Section [A’] – Prayer (5-7)

Grammatically, these āyāt also form one continuous sentence. We pray for guidance, then spend the rest of the prayer defining that guidance. We want to be guided like those before us (a show of mercy), not like those who incurred anger – the Arabic does not associate Allah ﷻ with the anger, which is another show of mercy – nor of those who went astray because of their lack of guidance.

Summarized another way, the ring can be presented as:

Taken altogether, we find that the first and last ring correspond to each other – mercy is emphasized twice in the center of each – and that the central āyah of the sūrah contains the main ideas of both rings.

Thus, we see that Sūrat al-Fātiḥah has a concentric structure, consisting of two corresponding outlying parts - themselves consisting of smaller rings - that enclose a central part relating to them both.

Just as interesting, we see that the sūrah is split perfectly between Allah ﷻ and us, His servants.

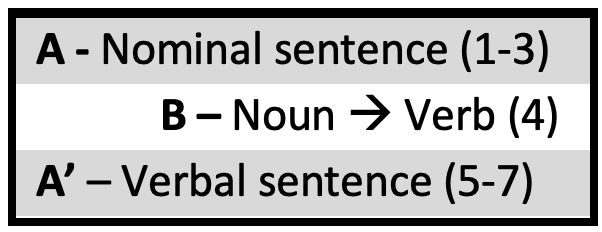

Delving deeper into the nuances of this sūrah, we find cohesion even on a grammatical level. Specifically, we find that the middle section, Section [B], links the two halves of the sūrah together from a grammatical point of view.

As mentioned earlier, Section [A] is one continuous sentence. Of particular note is that it is a sentence that begins with a noun, which makes it a nominal sentence7. In contrast, the final sentence, Section [A’], begins with a verb and is therefore a verbal sentence8.

Bridging these two parts together, the central āyah is made of two statements where the noun has been brought forward from where it would typically be in an Arabic sentence9. Thus, the two statements begin with a noun and end with a verb. This matches perfectly with the two sentences on either side of this āyah.

And finally, there is a rhetorical benefit to the grammatical structure of the sūrah. In Arabic, sentences that begin with nouns are considered independent and permanent10. In contrast, sentences that begin with a verb are considered dependent and time-bound11. It is astounding that the section that speaks of Allah ﷻ is nominal (as He is Permanent and Independent of all creation) and the section that describes us and our prayer is verbal (since we are mortal beings that are dependent on Allah ﷻ).

And Allah knows best.

The following is based on the works of:

Farrin, Raymond. Structure and Quranic Interpretation: a Study of Symmetry and Coherence in Islams Holy Text. White Cloud Press, 2014.

Mir, “Contrapuntal Harmony in the Thought, Mood, and Structure of Surat al-Fatihah,” Renaissance 9 (1999): 1-2

Sahih al-Bukhari 4647, https://sunnah.com/bukhari:4647

Ibn Kathīr, Tafsīr al-Qur’ān al-ʿĀẓīm, Sūrah al-Fātiḥah, https://tafsir.app/ibn-katheer/1/1, accessed 3/19/2022

For this, and all future structures, the numbers in parenthesis are the āyah numbers associated with each respective section.

The Bismillāh Ar-Raḥmān Ar-Raḥīm (with the help of Allah, the Most Loving and Merciful, the Ever-Loving and Merciful) found at the beginning of most suwar.

This one is dedicated to all my fellow followers of Imām Abū Ḥanīfah

In Arabic, this is called a jumlah ismiyyah

In Arabic, this is called a jumlah fiʿliyyah

In Arabic, this is called a mafʿūl bi-hi muqaddam

Because nouns do not need someone to do the action and are not time-bound.

Because verbs require someone to do the action and they only last as long as the action takes place.

Laa ilaaHa illallaaH